Virtual Reality: A New Perspective in Storytelling

As audiences, we are used to experiencing stories from a fairly privileged perspective — that of the all-knowing, all-seeing omniscient entity. We take in the events playing out on the stage or the screen as an impartial bystander, sometimes guided by a narrator or, in Greek theater tradition, a chorus who help us connect the dots and interpret the action taking place before us. Seeing everything unfold at once helps us better understand the interplay of relationships, situations and external forces that precipitate a certain plot point — the star-crossed lovers striving to be together against all odds; the vengeful conspirators plotting to ruin the hero's plan; the talented detective connecting every piece of the puzzle to crack a baffling case. Seeing things in context helps us understand the situation and the characters' motivations more completely.

Or does it? Perhaps a different vantage point — one that asks us to walk a mile in another man's shoes and experience a scene from a single character's perspective, could deepen or add nuance to the way we interpret the course of events? Virtual reality offers us the ability to immerse spectators in the action, often placing us in the virtual body of a character or bystander on the scene. As a result, it is increasingly, though controversially, explored as an “empathy machine” in various disciplines; for example, media art, journalism, and documentary film. Many creative practitioners are employing the technology to invent perspective-taking projects that are meant to affect us emotionally, empower and challenge us ethically, and (hopefully) expand our capacity for self-understanding.

Here, we’re taking a look at work by Karolina Ziulkoski, Rose Troche and Morris May, and BeAnotherLab as examples of the ways creative practitioners have been exploring this new realm.

Karolina Ziulkoski and Dulphe Pinheiro Machado, Vicious Circle

Vicious Circle, created by NEW INC member Karolina Ziulkoski, is a short film exploring the issue of domestic violence. The viewer, upon donning an Oculus Rift headset, finds him or herself at home with their partner. As the viewer “walks” around the living room, experiencing the scene through the point of view (POV) of the victim, a misplaced movement may accidentally bump a remote control off a table or trigger some other casual clumsiness. This small gesture elicits one of three reactions from your virtual partner — mild, verbally abusive, or physically abusive. Which reaction occurs is selected at random, a deliberate decision used by Karolina to create a state of insecurity, commonly experienced by victims of domestic violence. For Karolina, the immersive and empathy-inducing power of VR largely contributes to a compelling experience, “putting the user in such a situation makes it easier to understand the struggles of the victims, and makes them feel what it is like to be inside a domestic violence situation, something other media cannot provide as effectively.”

Karolina carefully considered not only VR’s immersive nature, but also the way people might perceive and interpret the situation based on various cues in the VR experience, and made conscious choices to keep things rather ambiguous. “Often when people think about domestic violence, they relate mostly to a couple — a man and woman, with the woman as victim and the man as perpetrator. But there are many other situations of domestic violence. For example, those on children,” says Karolina, “I don’t want to reduce it to a man-woman situation.” Rather than have the viewer inhabit a particular character, the film leaves the victim’s body invisible and open to the viewer’s imagination. In this sense, one has the feeling of embodying both the victim in the film and one’s own self.

Rose Troche and Morris May, Perspective 2: The Misdemeanor

Likewise, the VR film series Perspective by Rose Troche and Morris May also takes on a first-person POV in its storytelling approach. The directors utilize this viewpoint to help audiences see a story from the unique perspectives of all the characters in the scene, with the goal of allowing the viewer to gain a deeper understanding of the nuances, complexities, and ways tense situations can be misconstrued and misinterpreted. For example, the second chapter in this series, The Misdemeanor, lets viewers experience a fictionalized police shooting through the eyes of each person involved: a teenager who gets shot, his brother, and two officers. “It would be unrealistic of us to create this work without thinking of the other side... I didn’t want to make a piece that was only there to agitate,” Rose explained at NEW INC and Kill Screen’s VR Conference “Versions” recently.

Referencing the ongoing conversation in the media and online about police brutality, in which people on various sides of the issue seem to be drifting farther apart instead of bridging the gap of understanding, the piece is meant to challenge viewers’ preconceived notions of how these situations occur, and hopes to illustrate how they aren’t always so clear cut. In Misdemeanor, every character makes a mistake — some with graver consequences than others, some operating from positions of considerable privilege and power that may protect them from ever experiencing the full extent of their consequences. Watching the same scene unfold from each narrator’s perspective reveals how narrow and biased a first-person perspective can be.

By shifting the viewer’s perspective from bystander to protagonist, both Vicious Circle and Misdemeanor aim to highlight some often unaddressed (yet critical) emotional and psychological reactions that might prompt a deeper and nuanced understanding of these fraught social issues. Can these experiences help audiences tap into even a watered down version of the helpless mental state of a domestic abuse victim? Or consider the persistent state of anxiety and vulnerability that is the daily life of a black teenager and how that might propel his at once dismissive and defensive gestures? Can these experiences provide fresh insights into news headlines that have become all too familiar?

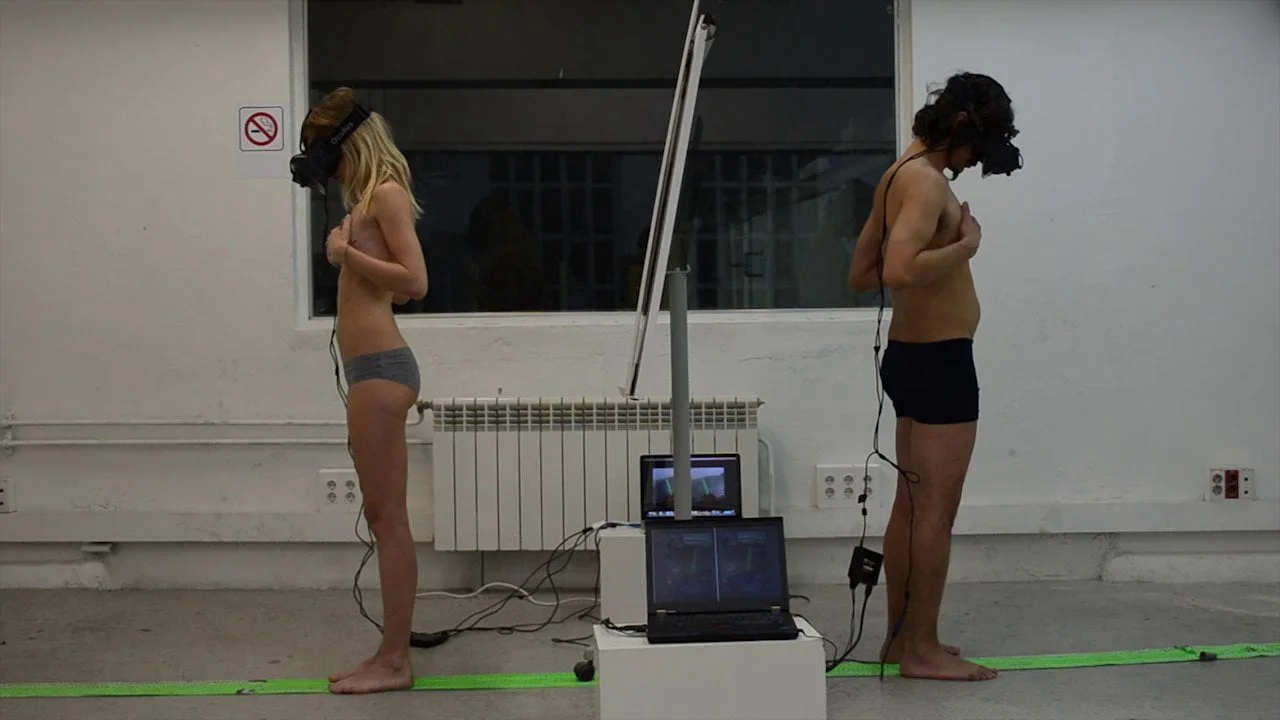

BeAnotherLab, Gender Swap

To take this thought experiment to its natural conclusion, what if instead of a pre-recorded scene or a fictionalized scenario, what if we could temporarily see through the eyes of another person in real-time? The Machine to be Another, an interactive performance installation created by the interdisciplinary collective BeAnotherLab, offers participants this possibility. Unlike the aforementioned two films, where the visuals, environments, and narratives are predetermined, the experience within this installation is not fully scripted and requires creative improvisation from participants. Gender Swap is one of the experiments that use the Machine system as a platform for embodied experience.

To create a visual-haptic illusion of being a different gender, users at both ends of the immersive headsets are required to synchronize their movements and constantly agree on every movement they make. In this case, projects using the Machine system sometimes are “not necessarily interested in the complete reconstruction of the subjective experience of ‘the other,’ nor only in straightforward social perspective-taking,” says Ainsley Sutherland in her case study published on MIT- Docubase. Instead, “they explore how the boundaries of the ‘self’ can be manipulated and perhaps expanded.” The intersubjective exploration of the “self” will thus lend itself to new approaches to issues including but not limited to gender identity, intimacy, and mutual respect.

Even as only a small sample of what’s being currently created, the above projects are utilizing VR as not only a powerful platform in storytelling, but also a tool to stimulate the viewer’s reflection on ethical issues, facilitate their communication with groups that they possibly do not identify with, and renew their self-awareness.

What also unites these three pieces is the potential risk that underlies the empathetic powers of VR. If this platform can indeed help practitioners achieve greater emotional affect than previous media and can make audiences feel more compelled to participate in endeavors for social good, is there a flip side? It’s one thing when the UN uses VR to tell the tale of displaced refugees but what if this same technology was used to magnify radicalism and enforce oppression when wielded as a tool of propaganda? This begs the question, who gets to take the authorial role in VR? Do we need systems to regulate how people use it? Who makes those calls and how far do we take them? While calling for censorship may be too severe, we have a social responsibility to consider more than just the generative process of storytelling if we want VR to move out of mere entertainment and spectacle and facilitate deeper inquiries into our humanity.

For further inquiry into the empathetic power of virtual reality, our Versions Panel “Does VR Need a Hippocratic Oath?” is worth a watch.

*Featured image via BeAnotherLab