Jason Eppink, Solving For Accessibility In Museum Design

His latest intervention is so natural you’ll wonder why it isn't ubiquitous.

Multicaptions (2017). Courtesy Jason Eppink.

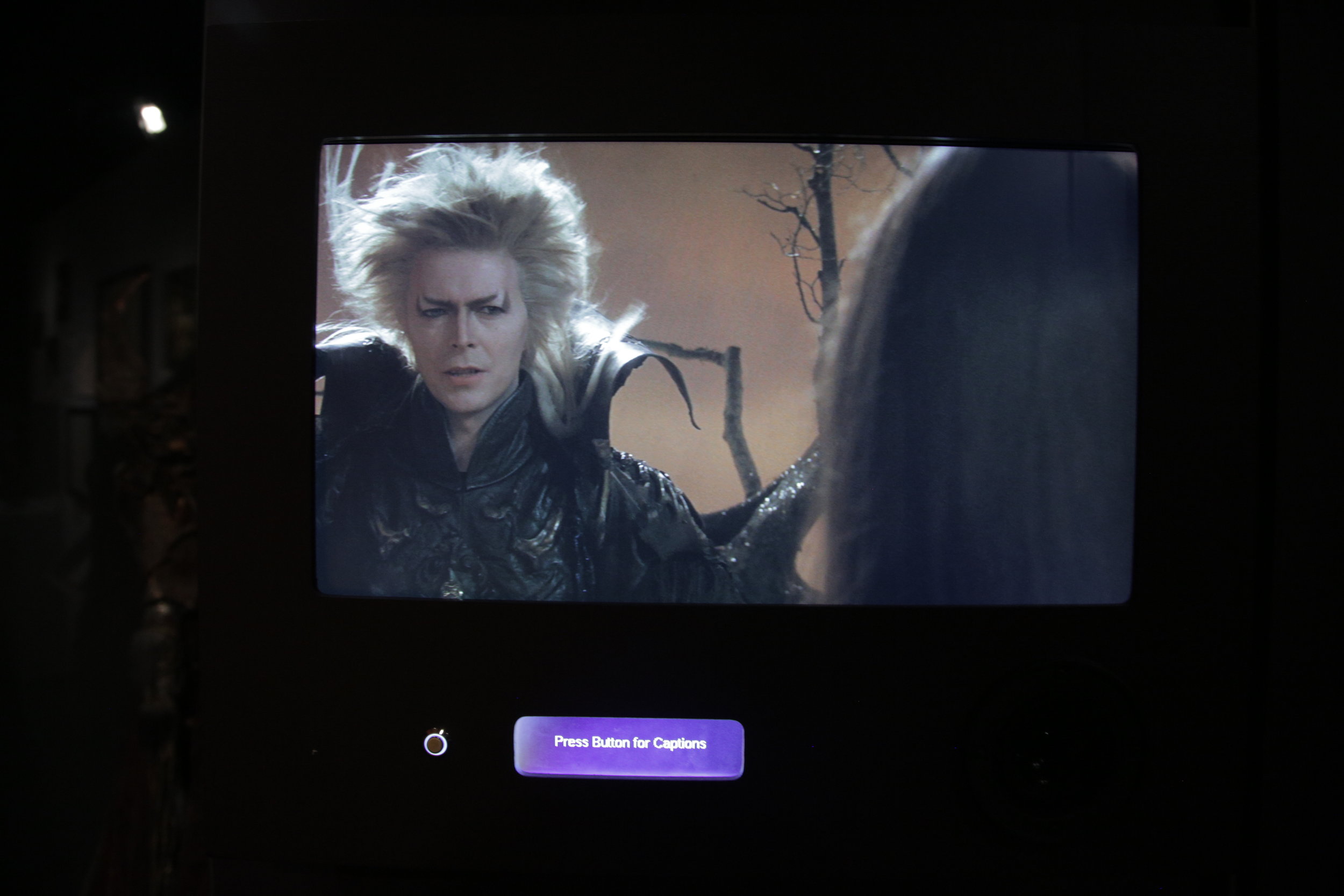

Over at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, nearly 300 puppets assembled by Jim Henson hang motionless in a permanent exhibition on the famed puppeteer. As viewers cross the floor, passing familiar faces like Kermit the Frog, Sesame Street’s Oscar the Grouch, and Labyrinth’s Lancelot, twenty-seven accompanying video monitors project the puppets in action. The room feels light, making it easy to overlook a subtle albeit significant feature that's unique to the show.

Beneath each of the video monitors lies an LCD bar with a silver button, which, when pressed, activates the closed captions. The device allows the user to toggle across languages. Once the selection has been made, the captions stream within visual range of the work itself, allowing the media to stand alone without the typical burnt white text.

The device is the brainchild of Jason Eppink, a creative technologist who currently works as the museum’s associate curator of digital media—and as he told NEW INC in a recent interview, he's hoping to supply other small but impactful interventions that make museum experiences more inclusive.

“I was unimpressed with how public institutions were addressing both accessibility for hearing-impaired viewers,” Eppink said. “But also an almost complete lack of translation services for video.”

Image from "The Jim Henson Exhibition" at the Museum of the Moving Image. Courtesy the author for NEW INC.

“The problem with [standard captioning] is that it’s a very specific aesthetic,” Eppink continued. “It purports to be neutral, but there is no such thing. It covers up a lot of image. It’s crazy that unless, as a director or cinematographer, you’re thinking about how the bottom quarter of your screen is going to have all this text, there’s a disconnect. That might be okay with contemporary artists who are thinking about the text below, but I deal with a lot of archival footage. Trying to show something that was on TV in the 50s, it really takes away from that feeling when you put that contemporary text on top of it.”

Recommended: Rapport Studios, Linking New York City's Top Culture Hubs To The People

A substantial portion of the ongoing collection at the Museum of the Moving Image is archival, which presents a unique challenge concerning how to caption non-contemporary works. Barbara Miller, the museum’s curator of collections and exhibitions, said that the need for a new approach to closed-captioning was long-coming.

“We feel that putting captions over the the work we want to share really interferes with the work itself, and is even disrespectful to the work,” Miller explained. “When the Henson exhibit rolled around, we had a lot of time to prepare leading up to it, and we knew it would be a very monitor-heavy exhibit. Jason really took the reigns with thinking through new approaches.”

Miller has also seen a positive response from visitors who have used Eppink’s tool. “It’s great, because you don’t have to look up and look down to see it all. It’s all in one field of vision,” Miller said. “This is something we hope to build on and apply in other galleries. We need to fully evaluate how visitors experience it, but thus far it’s been an exciting and successful vision.” The museum is currently collecting qualitative information from guests who use the service for it’s aesthetic, auditory, and linguistic uses.

Image from "The Jim Henson Exhibition" at the Museum of the Moving Image. Courtesy the author for NEW INC.

“A lot of museum tech is geared towards the top one percent of museums that can pay big dollars for fancy interactives,” Eppink noted. “That’s not what this is about. This is about how to make it really easy and cheap...With just a couple lines of Python and a Raspberry Pi, you can recreate [this] yourself, and that’s cheaper than investing in an actual media player.”

Eppink drew inspiration from The Metropolitan Opera’s closed captioning system, called Simultext, which provides multi-lingual captions on a screen in front of every seat, keeping the captions in eye-line to the performance. Aside from just the aesthetic purposes of stripping captions from a video piece, the technique of utilizing a separate screen allows users the individualized experience of selecting their own language—an innovation unprecedented in art museums.

Concerning linguistic accessibility, Eppink said that American museums fall decades behind in progress compared to other countries, adding that European museums have at least two languages in captions and museum copy as a general standard. In 2008, the Canadian Parliament launched the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, a center widely-recognized for setting the standard for institutional accessibility.

According to Museums and Heritage Advisor, the center includes "120 Universal Access Points (UAP), which have Braille, tactile numbers and “cane-stop” floor strips to alert visitors that information is available on key exhibit highlights. There is inclusive video and audio, a mobile app and innovations such as an Interactive Universal Keypad (IUK) for those who cannot use a Touch Screen Interface (TSI)."

Author: Annie Armstrong

Editor: Rain Embuscado