On Art, Technology, And Railing Against The Nicaragua Canal

How a Central American intervention is implicating the world.

Map of Central America. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Four years ago, in June 2013, Nicaragua’s president, Daniel Ortega, passed Law 840 through the National Assembly after private conversations between himself and Wang Jin, Beijing billionaire and CEO of telecom company Xinwei. The law provided the newly-formed infrastructure development firm HKND Group sovereignty over any part of the territory that fell under the proposed route for the Nicaragua Canal, which was billed as a “major infrastructure project with the potential to transform global trade, and make Nicaragua an important hub for transportation and logistics.”

The aspirational logic of this statement, pulled directly from HKND Group’s website, permeates the site’s rhetoric and aesthetics, as seen by the very first image of the home page:

Courtesy Creative Commons.

“The century-old dream will come true,” reads the banner, with an imposing image of a boat0full of cargo determined to sail prosperity and power across Nicaragua. It taps on a long-standing national lust affair with achieving “development” and “becoming modern.” As Volker Wunderich discussed in an essay titled, El nuevo proyecto del Gran Canal en Nicaragua: mas pesadilla que sueño, this current iteration is Nicaragua’s third attempt at building a canal, an attempt that seeks to mend the “humiliation” of not fulfilling the “natural destiny” dictated by the country’s geographic position in the isthmus.

If the current project for the canal can be understood as having stakes on the very entrance of Nicaragua into the world stage as a “developed” and “modern” country, a project that represents Nicaragua’s ability to define itself as a powerful sovereignty, Fredman Barahona and Guillermo Saenz’s Cartas Mojadas, an interactive performance art project that took place in Beijing during the winter of 2016 through China Residencies, provides a different Nicaraguan dream, one that reveals the lives that are rendered disposable in the process of reaching “national development.”

The project consisted of delivering to hutong residents in Beijing letters from fourteen campesinos that will be displaced if the construction of the canal takes place. The letters are accessible online, both in the original Spanish and English/Chinese translations, and the artists invite readers to submit their responses to be delivered back to Nicaragua. Reading the letters, one notices that most of them repeat the same request: asking the “Chinese people” to put themselves in “our shoes” and “protest with us.”

By uploading the letters and facilitating direct communication, the artists extend the cry for help to anyone and everyone who has access to the Internet. In-so-doing, Cartas Mojadas reveals the invisibility surrounding the violence that infrastructure projects inflict on local, indigenous lives, an invisibility that exists alongside with the legacy of Iberian colonialism and U.S imperialism in the region, not to mention the current wave of Chinese neo-imperialism.

The project brings attention to the injustices and damages that the canal will impose upon both socially and environmentally. It also underlines how unknown this is and how this condition of unknowingness facilitates the perpetuation of exploitation and death. When the letters ask to “put yourselves in our shoes,” they voice an attempt to mobilize knowledge about the fear and anger that is felt on the body of local Nicaraguans. In other words, the letters try to transgress the condition of unknowingness that inhibits the ability to even imagine oneself as the other.

The significance of Cartas Mojadas must also be thought of in relation to Central America’s historical exclusion from Latin American art. Kency Cornejo has discussed how “The invisibility of Central American art within Latin American art, at least until very recently, mirrors the invisibility of Central American migrants, whose experiences scholars have described as representing the “ambivalence of non-identity” (191). Cornejo links the exclusion of Central American cultural production from the label of Latin American art as another manifestation of the structural “non-placeness” that has come to define Central America, a condition that perpetuates the region’s “selling out” to private interests at the expense of people’s livelihood.

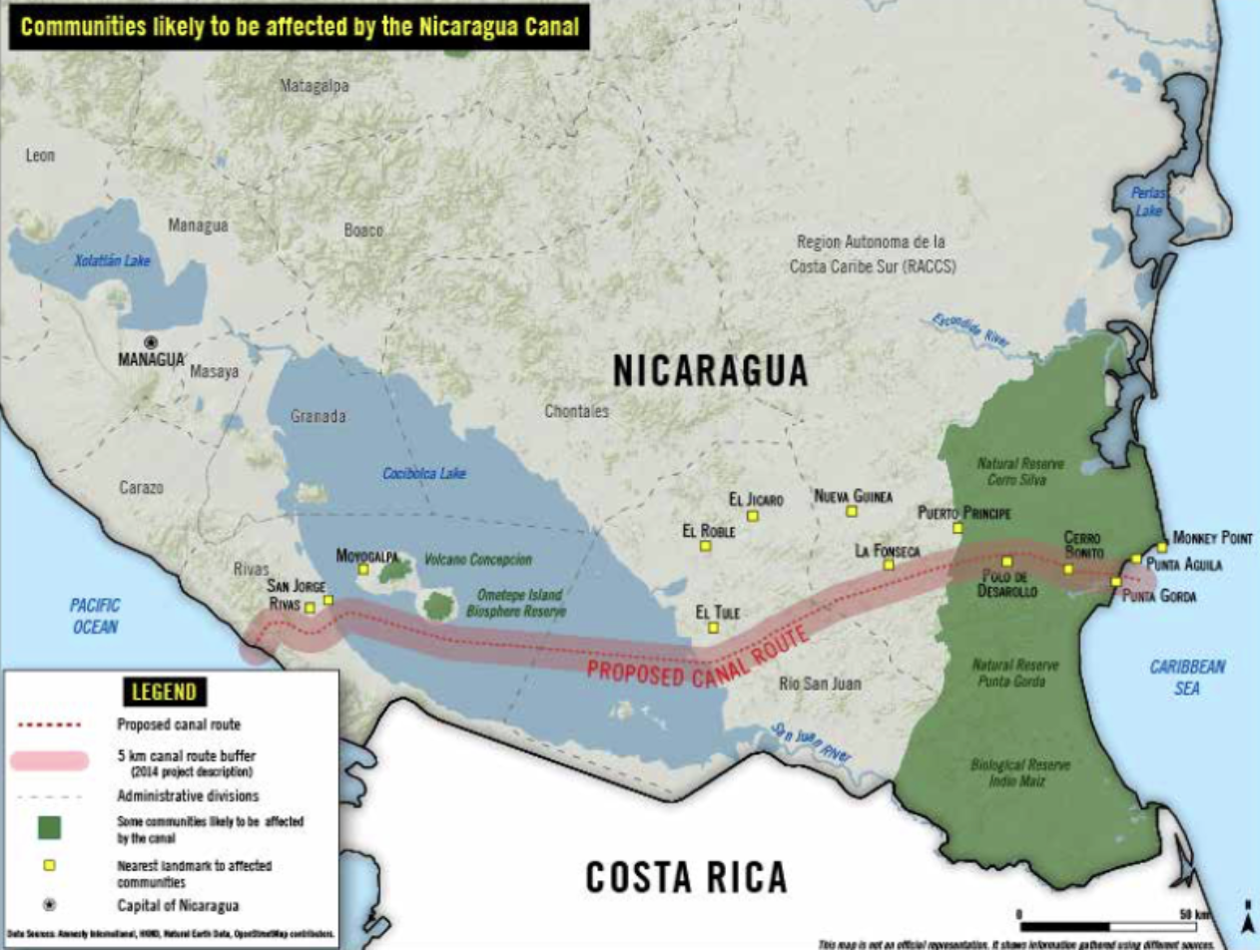

Map of the communities that will be affected by the canal, from Amnesty International’s August 2017 report. Although not explained in the map, most of the communities in green are indigenous communities, making the violence inflicted one that is mostly experienced by those who have historically been racialized as disposable. The lake the canal is planned to go through will also be polluted, rendering unusable the largest source of fresh water in Central America. Courtesy Amnesty International.

Cartas Mojadas therefore is a de-colonial aesthetic action that seeks to undo the historical colonial wound that has sought to constantly render indigenous people in Nicaragua as disposable by making known the conditions of uncertainty, of the non-placeness that structures their lives. The art piece enunciates a dream of a network of social actors on a global scale that works internationally to assert the local right to be and to exist, despite a threat that seeks to prove the opposite—the disposability of the local.

Editor: Evan Berk

Josue Chavez is an art and technology enthusiast, originally from Honduras. Chavez has worked with Basement6, a not-for-profit art space in Shanghai, and China Residencies. Chavez is also working on a mapping visualization project about the life of Dalit activist R.B More, and a digital collage about the blog of Susana Chavez, an activist-poet who was murdered in Ciudad Juarez.